Dr. Tauisi Minute Taupo

Secretary of Justice, Communications, and Foreign Affairs

Ministry of Justice, Communications, and Foreign Affairs

Government of Tuvalu

Private Mail Bag

Funafuti, Tuvalu

Telephone: (688) 20117

Email: [email protected]

Ms. Lafita Paeniu

Senior Adviser (Pacific Division)

Department of Foreign Affairs

Funafuti, Tuvalu

Telephone: (688) 20117

Email: [email protected]

Mr. Pasuna Tuaga

Deputy Secretary

Ministry of Justice, Communications, and Foreign Affairs

Private Mail Bag

Funafuti, Tuvalu

Email: [email protected]

Ms. Tilia Tima

Acting Director of Environment

Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Trade, Tourism

Environment and Labour

Private Mail Bag

Funafuti, Tuvalu

Telephone: (688) 20117

Email: [email protected]

Ms. Pepetua Latasi

Director of Climate Change Policy and Disaster Coordination Unit

Office of the Prime Minister

Government of Tuvalu

Private Mail Bag

Funafuti, Tuvalu

Email: [email protected]

Telephone (688) 20815/ 20517

Fax: (688) 20167/ 20836

Mr. Jamie Ovia

Senior Mitigation Adviser

Department of Climate Change Tuvalu

Private Mail Bag

Funafuti, Tuvalu

Email: [email protected]

Mr. Tauala Katea

Director of Meteorology and IPCC Focal Point

Tuvalu Meteorological Service

Private Mail Bag

Funafuti, Tuvalu

Email: [email protected] OR [email protected]

Telephone: (688) 20736

Date updated: April 2024

Capital: Funafuti

Land: 26 sq km

EEZ: 757,000 sq km

Population: 10,000 (2003 est.)

Language: English, Tuvaluan

Currency: Australian Dollar

Economy: Agriculture, fisheries and philatelic sales

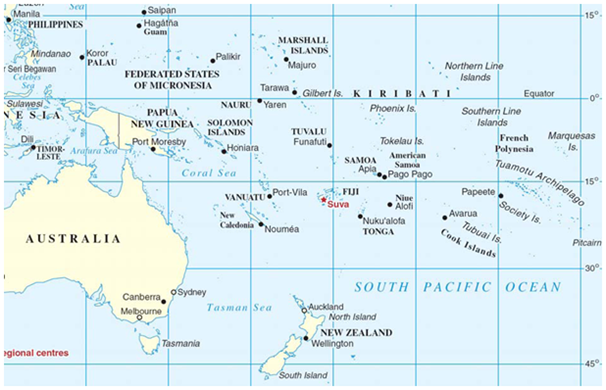

Tuvalu archipelago comprises nine small islands, six of them being atoll islands (with ponding lagoons) namely Nanumea, Nui, Vaitupu, Nukufetau, Funafuti and Nukulaelae. The remaining three islands, Nanumaga, Niutao, Niulakita, are raised limestone reef islands. All the islands are less than five meters above sea level, with the biggest island, Vaitupu, having a land area of just over 524 hectares. The total area is approximately 26 km2 with an EEZ of 719,174 km2.

Tuvalu is a Least Developing Country with a per capita income of less than USD4000, and is the smallest of any independent state. According to a world Bank (2013) report, Tuvalu’s gross domestic product (GDP), was estimated at USD 39.7 million in 2013 and was the smallest of any independent state. GDP growth in the past was volatile and this is expected to continue into the future due to Tuvalu’s dependence on fishing and internet domain licensing fees, remittances, and trust fund returns, all of which are dependent on exogenous factors beyond the government’s control. Due to the small population and lack of land area and resources, the scope for economic diversification, including exports, is minimal. Nearly everything, including skilled services, is imported. Fuel and food constitute nearly half of total imports of goods.

Source: ©SPC, 2013.

Date updated: March 2016

Current climate

Annual and May–October mean and maximum air temperatures at Funafuti have increased since 1933. The frequency of night-time cool temperature extremes has decreased and warm temperature extremes have increased. These temperature trends are consistent with global warming.

Annual and half-year rainfall trends show little change at Funafuti since 1927. There has also been little change in extreme daily rainfall since 1961.

Tropical cyclones affect Tuvalu mainly between November and April. An average of 8 cyclones per decade developed within or crossed the Tuvalu Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) between the 1969/70 to 2010/11 seasons. Tropical cyclones were most frequent in El Niño years (12 cyclones per decade) and least frequent in La Niña years (3 cyclones per decade). Only three of the 24 tropical cyclones (13%) between the 1981/82 and 2010/11 seasons were severe events (Category 3 or stronger) in the Tuvalu EEZ. Available data are not suitable for assessing long-term trends.

Wind-waves around Tuvalu do not vary significantly in height during the year. Seasonally, waves are influenced by the trade winds, extra-tropical storms and cyclones, and display variability on inter annual time-scales with the El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) and the strength and location of the South Pacific Convergence Zone (SPCZ).

Source: Australian Bureau of Meteorology and CSIRO, 2014.

Future Climate

For the period to 2100, the latest global climate model (GCM) projections and climate science findings for Tuvalu indicate:

- El Niño and La Niña events will continue to occur in the future (very high confidence), but there is little consensus on whether these events will change in intensity or frequency;

- Annual mean temperatures and extremely high daily temperatures will continue to rise (very high confidence);

- It is not clear whether mean annual rainfall will increase or decrease, the model average indicating little change (low confidence), with more extreme rain events(high confidence);

- Incidence of drought is projected to decrease slightly (low confidence);

- Ocean acidification is expected to continue (very high confidence);

- The risk of coral bleaching will increase in the future (very high confidence);

- Sea level will continue to rise(very high confidence); and

- December–March wave heights and periods are projected to decrease slightly (low confidence)

Source: Australian Bureau of Meteorology and CSIRO, 2014.

Date updated: March 2016

Governance

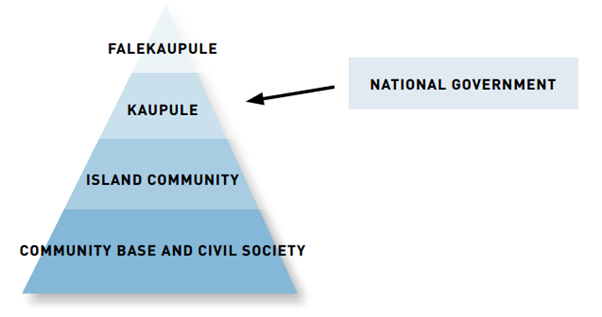

The National Government is the focal point of all national issues including climate change adaptations. These adaptation activities are to be undertaken at the Falekaupule level taking into account the 1997 Community Governance Arrangements. After December 12 1997, a new form of governance was established for all Island communities in Tuvalu. The new form of governance (Falekaupule Act of 1997), passed by the Parliament of Tuvalu, devolved the authority to the Falekaupule and Kaupule(two separate bodies) to work together in addressing community affairs in order to promote decentralization to decrease domestic urban drift.

The Falekaupule is the product of the fusion of the traditional leadership and the introduced governing system. It functions as the decision making body on the island. The Kaupule is the executive arm of the Falekaupule. The central Government links directly to the Kaupule as shown below.

The Department of Environment has implemented several environmental programmes and projects. Each programme has established task committees or teams with representation from relevant and major Governmental departments, Non-governmental Organisations (NGOs), religious bodies and stakeholders.The Development Coordinating Committee (DCC) that was setup under the Office of the Prime Minister, and chaired by the Secretary to Government assesses draft policies, projects and programmes prior to submission for approval by Cabinet.

The implementation arrangements for Te Kaniva: Tuvalu Climate Change Policy (TCCP) and the National Strategic Action Plan for Climate Change and Disaster Risk Management (NSAP) partly follow the currently established arrangements and suggest a merging of the two national committees responsible for coordinating climate change and disaster risk management in Tuvalu. The suggested merging was developed through consultations with the Tuvalu expert team working on the TCCP and NSAP and through consultation with a number of Chief Executives and senior officials within Government.

Currently, climate change and disaster risk management have two separate institutional arrangements although the positions and the holder inside these two arrangements may be the same. The National Disaster Management Act stipulates the institutional arrangements for disaster risk management (DRM). In the event of an emergency or disaster the structure is:

The National Disaster Committee (NDC) is coordinated by the National Disaster Management Office (NDMO) which is housed in the Office of the Prime Minster. The Minister responsible to Government on all disaster related matters shall ensure that all government agencies have taken adequate measures to mitigate, prepare, respond to and recover from disasters and foster the participation of non-government agencies in disaster risk management arrangements taken by government (Part 2 National Disaster Management Act).

As mentioned above, the climate change portfolio is under the Department of Environment as provided by the provisions of the 2008 Environment Act. The Department of Environment provides the overarching coordination and advisory role for climate change related projects through a National Climate Change Advisory Committee (NCCAC).

The NCCAC is an inter-ministerial/department and sectoral committee that also has members from the civil society and NGOs, as well as outer islands representatives. The Development Coordination Committee (DCC) is under the Ministry of Finance where projects for donor funding are priorities and submitted to Cabinet for approval. Under the umbrella of the NCCAC, there are climate change and relevant projects that are coordinated by other government agencies.

The NSAP includes an action that looks in detail at the institutional arrangements of DRM, Climate Change and Meteorology. There is value in these three institutions working collaboratively to ensure timely sharing of data, information and expertise to support adaptation and disaster risk reduction planning.

Date updated: March 2016

National Climate Change Priorities

Te Kakeega II (2005 – 2015) is Tuvalu’s National Sustainable Plan. It contains nine themes and strategic actions including:

- good governance

- strengthening macroeconomic stability

- improving the provision of social services

- improving outer islands development and Falekaupule

- creating employment opportunities and enhancing private sector development

- improving capacity and human resource development

- developing Tuvalu’s natural resources

- improving the provision of support services

- mainstreaming of women in development.

The Te Kaniva(Tuvalu Climate Change Policy) prescribes the Government and the people of Tuvalu’s strategic polices for responding to climate change impacts and related disaster risks over the next 10 years (2012–2021). The policy outlines seven priorities which are:

- Strengthening Adaptation Actions to Address Current and Future Vulnerabilities

- Improving Understanding and Application of Climate Change Data, Information and Site Specific Impacts Assessment to Inform Adaptation and Disaster Risk Reduction Programmes.

- Enhancing Tuvalu’s Governance Arrangements and Capacity to Access and Manage Climate Change and Disaster Risk Management Finances

- Developing and Maintaining Tuvalu’s Infrastructures to Withstand Climate Change Impacts, Climate Variability, Disaster Risks and Climate Change Projection

- Ensuring Energy Security and a Low Carbon Future for Tuvalu

- Planning for Effective Disaster Preparedness, Response and Recovery

- Guaranteeing the Security of the People of Tuvalu from the Impacts of Climate Change and the Maintenance of National Sovereignty

The Te Kaniva is formulated with the understanding that Tuvalu’s development partners and the international community will help support its’ financing and implementation as presented on the Tuvalu Blue Print – Adaptation (2008). The Te Kaniva implementation, monitoring and evaluation arrangements are presented in detail in the National Strategic Action Plan for Climate Change and Disaster Risk Management (2012–2016) (NSAP). The Te Kaniva is a ten year policy (2011-2020) while the NSAP is a five year action plan (2012–2016). This is to ensure that the action plan is regularly monitored to keep it relevant to national priorities.

Date updated: March 2016

Adaptation

The first priority of the five year NSAP (2012-2016) addresses climate change adaptation. It is strengthening adaptation actions to address current and future vulnerabilities. There are four strategies to strengthen adaptation and they are in the thematic areas of health, food security, water resources and coastal resource management. The NSAP is clear of the lead agencies and partner agencies responsible for actions required of each strategy. For information on the agencies involved, go to [NSAP file link]

The actions for each strategy are provided in the below tables:

Adaptation Strategy | Actions |

HEALTH

Health and socio-economic implications (inclusive of gender) of climate change and disaster risks informing appropriate health and socio-economic adaptation programmes for each islands. | 1.1.1 Conduct assessment of health and socio economic implications of climate change and disaster risks in each island 1.1.2 Create awareness of results and make avail available in the database developed in 2.4.3 including gender disaggregated data and information 1.1.3 Develop adaptation programmes for funding based on the recommendations of the assessment in 1.1.1 1.1.4 Organise annual donor roundtables to discuss national projects 1.1.5 Conduct ongoing monitoring and annual evaluation of project status to enhance project implementation and to inform new initiatives 1.1.6 Upgrade and/or procure water quality testing equipment and make available to all islands 1.1.7 Provide training for sanitation aids on the use of equipment (1.1.6) |

FOOD SECURITY

Assessment and analysis of salt and/or heat tolerant food crops (e.g. pulaka) and tree species for coastal protection. | 1.2.1 Conduct research on current and other possible food crop and tree species on their salt and/or heat tolerance capability 1.2.2 Develop nurseries to nurture selected food crop and tree species that are salt and heat tolerant 1.2.3 Create awareness and distribute planting materials of the food crop and tree species that are salt and/or heat tolerant 1.2.4 Support organic vegetable and food crops gardening and the use of composting 1.2.5 Conduct applied research in collaboration with SPC and SPREP on pest management and control of invasive species |

WATER SECURITY

Integrated and coordinated water resources (including desalination) planning and management including preparedness and response plans for each island. | 1.3.1 Assess water availability and feasibility of water security options including rain water harvesting, underground water and desalination on all islands. 1.3.2 Implement improved rain water harvesting, access to underground water and install energy efficient desalination on all islands. 1.3.3 Prepare awareness materials on water conservation and safety 1.3.4 Implementation of these actions relevant to water resources are to be consistent with the National Water Policy, Integrated Waters Resource Management (IWRM) Plan and other water related plans, Public Health Act (Water Sector) and relevant recommendations from previous studies. 1.3.5 Develop drinking water safety components for the Island Strategic Plans (ISPs) 1.3.6 Develop a national IWRM Plan |

COASTAL RESOURCE MANAGEMENT Coordinated planning and management of marine, coastal and land resources and systems (Whole Island Systems Management/Ecosystem base management) | 1.4.1 Create awareness on the inter-linkages of marine, coastal and land ecosystems 1.4.2 Integrate climate change adaptation into the programme of work on protected areas including the development of protected areas on all islands 1.4.3 Review, update or develop new policies, local government bylaws and legislations on sustainable marine, coastal and land system management 1.4.4 Build enforcement capacities in responsible agencies (e.g. Ministry of Lands and Survey, Department of Environment, Department of Fisheries, Department of Health, Department of Agriculture) to implement 1.4.3 1.4.5 Conduct training for institutions responsible for coordinated planning and management in these areas. 1.4.6 Conduct assessments on state of marine, coastal and land resources/ecosystems and share this information with relevant sectors, and translation for local communities 1.4.7 Assess and address the impacts of land base practices including runoff and ground water leaching on the marine environment in context of climate change. 1.4.8 Assess and seek international support for reducing the impacts of climate change (such as temperature increase, ocean acidification, and changing pattern of circulation and ocean saturation) on coral reef, seagrass, algae, mangroves and other ecosystems. 1.4.9 Undertake urgent coastal protection measures incorporating soft options, natural island formation and assessed structural protection where appropriate |

Source: GOT, NSAP 2012

For information on climate change adaptation projects, visit the Climate Change Projects Database.

Date updated: March 2016

Mitigation

Goal 5 of the NSAP is ensuring national energy security and a low carbon future for Tuvalu. It has four strategies and actions as follows:

Mitigation Strategy | Actions |

REDUCE DEPENDENCY ON FOSSIL FUELS

Reduce reliance on fossil fuels by providing opportunities for renewable energy (RE) and energy efficiency (EE | 5.1.1 Conduct training and awareness programmes and demonstrate energy efficiency and conservation measures and practices. 5.1.2 Promote and encourage the use of solar Photo Voltaic systems and other appropriate renewable energy sources 5.1.3 Install solar PVs in all islands based on the result of feasibility studies |

PROMOTE PROGRAMMES ON EE AND ENERGY CONSERVATION

Promote energy efficiency and conservation programmes | 5.2.1 Develop awareness materials and programmes suitable for the schools (including vocational) in Tuvalu. 5.2.2 Develop awareness material and communication strategy for the public and communities including outer islands and deliver these programmes to ensure wide outreach and maximise the use of available media outlets |

DEVELOP LEGISLATION AND REGULATIONS ON EE and RE

Energy legislations and regulations promoting and supporting EE and RE | 5.3.1 Review and/or develop enabling legislation and regulations to promote and enforce energy efficiency (EE) and renewable energy (RE) opportunities. 5.3.2 Review other relevant legislation impacting on energy sector to align with the energy policy. 5.3.3 Develop an Energy Bill. |

| DEVELOP MITIGATION PLANS | 5.4.1 Conduct feasibility studies on using landfill and pig waste to generate methane 5.4.2 Implement methane recovery and use projects on all islands 5.4.3 Conduct training on technology know how and maintenance. |

Source: NSAP, GOT 2012

Greenhouse Gas Emissions

The Energy sector is the major contributor to C02 emissions (100%). The Waste sector is the main contributor of CH4 emissions (74.7%) followed respectively by the Agriculture sector (24.7%). On a mass basis, emissions of C02 are the most important. This is largely due to the importance of fossil fuel combustion as a source of CO2. Land-use change and forestry, is not an important CO2 source in Tuvalu. IN terms of carbon dioxide equivalent, Tuvalu’s gross aggregated GHG emissions (not including the LUCF sector), across all sectors, totalled 16. 95 Gg CO2-e in 2002 and the net GHG emissions (including the LUCF sector) were practically the same figures (16.92 Gg CO2-e).

Within the energy sector, emissions from electricity generation contribute to 41%, transport sector 40% and the remaining 18% from other sectors.

One of the main constraints to development is Tuvalu’s high dependency on imported energy sources, primarily petroleum products. Tuvalu has no conventional energy resources and is heavily reliant on imported oil fuels for transport, electricity generation and household use. High fuel pricses and fluctuations have a destabilizing effect on businesses and households, limiting growth and reducing food security, especially in the most isolated outer islands.

Renewable energy resources such as solar, wind, biomass and ocean energy are recognized as potential energy alternatives in the country. In the response to the world oil market and to ensure enhanced energy security, the Government of Tuvalu (GOT), committed to get 100% of its electricity from renewable energy sources by 2020. The Tuvalu National energy Policy (TNEP), formulated in 2009, and the Energy Strategic Action Plan defines and directs current and future energy developments so that Tuvalu can achieve the ambitious target of 100% RE for power generation by 2020.

Tuvalu’s Master Plan for Renewable Energy and Energy Efficience (TMPREEE) 2012-2020, outlines the way forward to generate electricity from RE and to develop an EE program. It has two (2) stated goals:

- To generate electricity with 100% renewable energy by 2020, and

- To increase energy efficiency on Funafuti by 30%.

According to TMPREEE, Tuvalu must develop 6MW RE electricity generation capacity in the next eight years. The initial capital cost of solar arrays, wind turbines and batteries to replace the current energy demand is estimated to be A$52million.

By the end of 2012, the output capacity of RE electricity generation using PV technology totalled a mere 146 kW (peak). There has been a steady increase int eh installations over the last 3 years and the country is tracking well in terms of meeting its target by 2020. The remaining time will be used to make any shortfall due to production efficiencies, weather conditions (that will affect available renewable resources) and other demands from the consumers.

Large scale implementation of energy efficiency improvements will also help reduce the electricity demand. Given the steady and continuing increase in the price of diesel oil, the RE electricity and the EE program will not only be cost effective but will ensure that affordable electricity is available to the people of Tuvalu.

It is estimated that following the completion of the RE and EE program, the use of the diesel generator plant will reduce by up to 95% with a consequent reduction in diesel fuel consumption. Savings in diesel fuel over the 30 year life of the overall programme are estimated to be A$152 million (2011 dollars) assuming oil prices continue to increase at the current long term trend. After allowing for battery replacements and other maintenance, which are estimated to cost A$115 million, the net saving over the 30 year programme will be A$37million.

Whilst the focus in RE has largely been solar through PVs, Tuvalu is ready to embrace other technologies, for example harnessing ocean energy, once these become available and affordable.

Planned Mitigation Actions

1. Renewable Energy

To meet the above objectives, Tuvalu will generate electricity using RE in all 9 islands of Tuvalu. The Outer Islands are being developed as a priority because fuel transportation from Funafuti increases the cost of generation and has environmental risks associated with potential fuel spill. Furthermore, the Outer Islands generate 18 hours a day (rather than 24 hours) and the power systems are less reliable.

On Fogafale, the main island of Funafuti atoll, due to the high population density, available land is scarce and ground-mounting of the proposed PV arrays that will form the major component of the RE electricity system is not considered practicable. In order to provide the required area for the PV arrays, a 1,000 Solar Roof Programme was proposed by Tuvalu Electricity Corporation (TEC). The project will see about half of the current roof space of the buildings in Funafuti occupied by PV arrays. In the case of the Outer Islands, a mix of roof mounted and ground mounted arrays will be adopted as there is ample space on those islands.

A wind energy feasibility study was carried out by the government with support from the World Bank and found good potential for wind energy around parts of Funafuti atoll and could offer significant technical and economic benefits. Wind turbines are planned for installation from 2016 onwards. A wind-solar mix will optimize the level of battery storage and level of diesel use for standby diesel generation as back up required.

Conversion or replacement of the existing diesel generators to run on bio-diesel fuel was proposed to take place and estimated that 5% of the annual electricity production will be supplied from bio-diesel generation. These plans are incumbent upon the development of a master plan for the coconut industry.

The following Table summarises the status of main energy installations in Tuvalu:

| Table: Summary of Power systems in Tuvalu | ||||

| Stations | Diesel Capacity (kW) | Solar Capacity (kW) | Comments | |

| 1 | Nanumea | 144 | 195 | actual output approx. 90% |

| 2 | Nanumaga | 144 | 205 | actual output approx. 90% |

| 3 | Niutao | 144 | 230 | to be online by end 2015 |

| 4 | Nui | 120 | 60 | actual output approx. 60% |

| 5 | Vaitupu | 144 | 400 | to be online by end 2015 |

| 6 | Nukufetau | 120 | 77 | actual output approx. 60% |

| 7 | Nukulaelae | 60 | 45 | actual output approx. 60% |

| 8 | Funafuti | 1200 | 735 | connected to grid, no storage |

| Total | 2076 | 1947 | ||

| Proposed World Bank Project 2015-2017 | ||||

| 9 | Solar | 925 | ||

| 10 | Wind | 200 | ||

| TOTAL | 2076 | 3072 | Total : 5.148 MW | |

2. Energy Efficiency

Energy Efficiency (EE) improvements will be initially targeted on Funafuti with a higher power demands per capita than the outer islands and also consumes 85% of the electricity generated by TEC.

Meeting the 30% target will allow Tuvalu to maintain current generation levels over the next eight years at 2% annual growth of GDP. The EE program will include publication education, energy audits and technology improvements. A proposed World Bank project is aimed at providing additional energy generation from solar PV and will include investment in modest wind-power capacity. Even if various reasons, the role of win in Tuvalu’s future power mix is likely to be smaller than solar PV. It will as serve as an important capacity building in this technology for TEC. The solar PV investment will provide sufficient battery storage and a power-conditioning system to ensure grid-stability, as intermittent RE sources become an increasingly dominant portion of Fogafale’s power mix.

In addition, the project will finance strategic EE investments in the largest electricity consuming sector. These investments could significantly reduce the need for future investments on the generation side. Moreover, the project will bring a longer-term perspective on RE investments from all sources by including battery storage and grid-forming inverters that represent major investments but are critical for long-term grid stability. Thus, this project will facilitate the planned and other future incremental RE additions without leading to grid instability and other system problems that would seriously set back the country’s plans toward achieving the 100% goal penetration of RE in the future.

3. Plans, Policies and Regulations

Under a proposed EE Act, the government will introduce legislation to promote EE and control the importation, use and sale of inefficient electrical appliances into the country. Under the EE Regulations 2015, which came into effect 1 January 2016, Minimum Energy and Performance Standards and Labelling (MESPL) will determine importation and use of appliances and goods. This is in line with GOT’s objective to promote EE, energy conservation and the use of Resources as part of Tuvalu’s obligations under the UNFCCC and related conventions.

Intended Nationally Determined Contributions

Tuvalu commits to reduction of emissions of green-house gases from the electricity generation (power) sector, by 100%, i.e., almost zero emissions by 2025.

Tuvalu’s indicative quantified economy-wide target for a reduction in total emissions of GHGs from the entire energy sector to 60% below 2010 levels by 2025.

These emissions will be further reduced from the other key sectors, agriculture and waste, conditional upon the necessary technology and finance.

Tuvalu’s targets go beyond those enunciated in Tuvalu’s National energy Policy (NEP) and the Mauro Declaration on Climate Leadership (2013). Currently, 50% of electricity is derived from renewables, mainly solar, and this figure will rise to 75% by 2020 and 100% by 2025. This would mean almost zero use of fossil fuel for power generation. This is also in line with our ambition to keep the warming to less than 1.5 degrees Celsius.

Tuvalu focuses the INDC on mitigation alone, while its adaptation actions continue to be comprehensively articulated in other national documents such as the NAPA, National Communications, and National Strategic Action Plan for Climate Change and Disaster Risk Management, National Climate Change Policy. The government plans to develop its National Action Plan in 2016.

Type and level of commitment: Electricity (power) sector and energy sector

Reference year or period: Start: 2020, End: 2025

Estimated quantified emissions impact:

- Reduce GHG emissions by 100% from the electricity sector by 2025.

- Reduce GHG emissions from energy sector by 60% below 2010 level by 2025.

| Coverage | % of national emissions (as at 2015) | Approximately 100% |

| Sectors | Energy sector:

Agriculture Waste | |

| Gases | Carbon dioxide, methane. Others are negligible | |

| Geography | Whole country (includes all outer islands) | |

| Further information, relevant to commitment type | e.g., annual estimated reductions, methodologies and assumptions for determining BAU or intensity baseline, peaking year | |

Intention to use market based mechanisms to meet commitments | NO | |

| Land sector accounting approach | N/A | |

| Metrics and Methodology | Consistent with methodologies use din Tuvalu’s Second National Communications (currently being finalised) using the 1996 IPCC Guidelines for GHG Inventory. | |

Planning Process

| Tuvalu adopted an all-inclusive process of engaging relevant stakeholders through bilateral consultations and workshops. The first workshop involving key Departments and Ministries provided much needed awareness about INDCs and the provision of additional data/information. It strengthened the whole-of-government process by providing national ownership of the INDC, as well as helped realise the synergies between other processes, including National Communications, National Energy Policy, and National Strategic Action Plan for Climate Change and Disaster Risk Management (2012-2016), National Strategic Plan and externally funded development projects in related areas. The second national consultation was used for the validation of the proposed targets contained in Tuvalu’s INDC, before it was presented for approval for National Advisory Council on Climate Change (NACCC) and endorsement by Cabinet prior to its submission to UNFCCC | |

| Fair and Ambitious | Tuvalu’s emissions are less than 0.000005% of global emissions, one of the lowers from any Parties, negligible in the global context. The import of fossil fuels into the country is used as proxy for the GHG emissions. The total fuel imports remained almost constant at around 3,500 kL, form 2001-2012. It declined by about 14% in 2013, but increased by approximately 23% in 2014 mainly due to the increase in the number of ships servicing the outer atolls. However, the figures for 2015 are showing significant decline in emissions due to the installation of new solar PV systems. Tuvalu is the world’s second lowest-lying country and sea level rise poses a fundamental risk to its very existence. Climate change through rising temperatures and irregular rainfall are already impacting on income from fish and crops. In this context, the target of zero dependence on important fossil fuels for electricity generation by 2025 cannot be more ambitious. Moreover, its targets to reduce emissions from the other energy sectors, mainly transport, are significant given that this is one of the most rapidly growing sources of carbon emissions. | |

For more information, go to: http://www4.unfccc.int/submissions/INDC/Published%20Documents/Tuvalu/1/TUVALU%20INDC.pdf

Date updated: March 2016

References

In the preparation of this country profile, primary sources (national documents) were used as much as possible. Where primary sources were not available, the following secondary and tertiary sources were used. It is important to note that contributions are from local, regional and international agencies. The profile is reviewed by the national focal point for accuracy. We encourage you to contact the country contacts (focal points) if any documents cannot be accessed through the links or any information is outdated.

- Australian Bureau of Meteorology and CSIRO (2014). Climate Variability, Extremes and Change in the Western Tropical Pacific: New Science and Updated Country Reports. Pacific-Australia Climate Change Science and Adaptation Planning Program Technical Report, Australian Bureau of Meteorology and Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, Melbourne, Australia

- Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific, United Nations, July 2007.

- Pacific Disaster Net

- Forum Secretariat website

- Tuvalu INDC

Date updated: March 2016