Ms. Elizabeth Jacob

Deputy Secretary for Pacific Affairs Division

Department of Foreign Affairs & Trade

Republic of Nauru

Central Pacific

Telephone: (674) 5573875

Email: [email protected]

Ms. Jaala Jeremiah

Director for Water Resource Management

Department of Climate Change and National Resilience

Republic of Nauru

Central Pacific

Telephone: (674) 558-8049

Email: [email protected]

Mr. Bryan Star

Director for Environment

Department of Commerce, Industry & Environment

Yaren District

Republic of Nauru

Telephone: (674) 5573900/ 5566053

Email: [email protected]

Mr. Reagan Moses

Secretary

Department of Climate Change and National Resilience

Email: [email protected]

Ms. Evalyne Detenamo

Secretary

Director of Climate Action

Republic of Nauru

Email: [email protected]

Date updated: April 2024

Capital: Yaren

Land: 21 sq. km

EEZ: 320,000 sq. km

Population: 9,233 (2006)

Language: English, Nauruan

Currency: Australian Dollar

Economy: Phosphate

The Republic of Nauru is one of the smallest independent, democratic states in the world. It is a republic with a Westminster parliamentary system of government but with a slight variance as the President is both head of government and head of state. The island is small, isolated, coral capped with 21 km2 in area, 20 km in circumference, located in the central Pacific Ocean 42 km south of the equator and 1287 km west of the International Date Line. Ocean Island (Banaba) is its nearest neighbour.

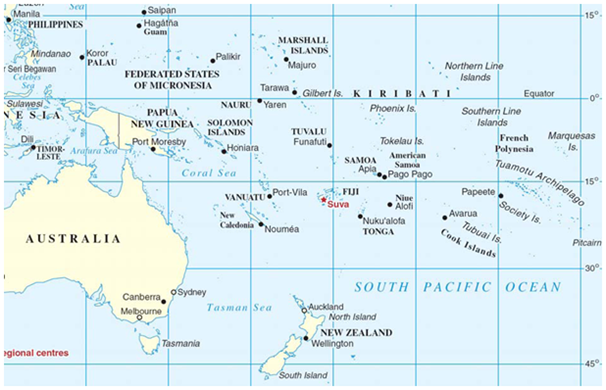

Nauru is a small single oval-shaped and raised coral equatorial island, located about 40 kilometres (km) south of the Equator at 0° 32’ 0” S, 166° 55’ 0” E. Its total land area is 21 square kilometres (km2) with an Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) of 320 000 km2. The island is divided into two plateau areas – “bottom side” a few metres above sea level, and “topside” typically 30 metres higher. The topside area is dominated by pinnacles and outcrops of limestone, the result of nearly a century of mining of the high-grade tricalcic phosphate rock. The bottom side consists of a narrow coastal plain that is 150 – 300 m wide as well as surrounded by coral reef, which is exposed at low tide and dotted with pinnacles. The bottom side is the residential area for the Nauru populace. The highest point of the island is 65m above sea level. The island lies to the west of Kiribati; to the east of Papua New Guinea (PNG); to the south of the Marshal Islands and to the north of the Solomon Islands.

The climate is equatorial and maritime in nature. There have been no cyclones on record. Although rainfall averages 2 080 mm per year, periodic droughts are a serious problem with only 280 mm of rainfall in the driest year recorded. Land biodiversity is limited, with only 60 species of indigenous vascular plants. A century of mining activity in the interior has resulted in the drainage of large quantities of silt and soil onto the reef, which has greatly reduced the productivity and diversity of reef life. Sewage is dumped into the ocean just beyond the reef, causing further environmental problems, while the island’s many poorly maintained septic tanks have contaminated the ground water. Access to fresh water is thus a serious problem on Nauru with potable water coming only from rainwater collection and reverse osmosis desalination plants. These desalination plants used around 30% of the energy generated by Nauru Utility Corporation (NUC) in 2008.

The main driver of climate variability in Nauru is the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO). La Niña events are associated with delayed onset of the wet season and drier than normal wet seasons, often resulting in an extended drought. During El Niño, temperatures on Nauru are warmer than normal due to warmer sea temperatures; and rainfall and cloud amount are increased. Another key climate driver for Nauru is the Inter-tropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ). The ITCZ affects Nauru all year round. Its seasonal north/south movement drives the seasonal rainfall cycle, which peaks in Dec-Feb. The South Pacific Convergence Zone (SPCZ) affects Nauru during its maximum northward displacement in July and August.

The 2012 census shows a population of 9,945 persons of whom 90.8% are ethnic Nauruan. The population has fallen since 2002 mainly due to a fall in the number of expatriate workers, mostly from Kiribati and Tuvalu, who began leaving Nauru as the island’s phosphate production dwindled. The main economic sector used to be the mining and export of phosphate, which is now virtually exhausted. The island has been mined extensively in the past for phosphate. Few other resources exist and most necessities are imported from Australia. Small scale subsistence agriculture exists within the island communities.

Nauru is faced with serious economic challenges. Its once thriving phosphate industry has ceased operation thus depriving Nauru of its major lifeline revenue source. The local infrastructure, including power generation, drinking water and health services, has been adversely affected in recent years by the decline in income from phosphate mining. However, further explorations of the residual phosphate deposits have raised hopes that there may be potential to keep the phosphate mining for yet sometime. With fewer prospects in the phosphate industry, Nauru has to look at other alternative revenue sources to support its economic development. Unfortunately, for a country of the size of Nauru (21 km2) with its limited natural resources, the options are not many.

Fresh water is also a serious problem on Nauru with potable water coming only from rainwater collection and reverse osmosis desalination plants. Nauru is a permeable island with very little surface runoff and no rivers or reservoirs. Potable water is collected in rainwater tanks from the roofs of domestic and commercial buildings. Water for non -potable uses is obtained from domestic bores at houses around the island. Shallow groundwater is the major storage for water between rainy seasons. There is increasing salinity in the groundwater bores around the perimeter of the island, and increasing demand for groundwater water due to development. Groundwater is contaminated by wastewater disposal from houses, shops, commercial buildings and RPC. Nauru now is highly dependent on donor support especially from Australia, Japan, New Zealand and Taiwan (ROC). It is important that Nauru develops and strengthens its partnership arrangements with the above countries to be able to meet the goals of its national development strategies which have identified key areas to be targeted in order to achieve some degree of economic stability.

The Government has prioritized reforms in the electricity and water sectors and in the management of fuel. With the recent adoption of its National Energy Policy additional legislation will be developed as required to provide a clear and practical path towards sustainable development.

Source: ©SPC, 2013.

Date updated: March 2016

Current climate

Warming trends are evident in annual and half-year mean air temperatures for Pohnpei since 1951. The Yap mean air temperature trend shows little change for the same period.

Extreme temperatures such as Warm Days and Warm Nights have been increasing at Pohnpei consistent with global warming trends. Trends in minimum temperatures at Yap are not consistent with Pohnpei or global warming trends and may be due to unresolved in homogeneities in the record.

At Pohnpei, there has been a decreasing trend in May–October rainfall since 1950. This implies either a shift in the mean location of the Inter-Tropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) away from Pohnpei and/or a change in the intensity of rainfall associated with the ITCZ.

There has also been a decreasing trend in Very Wet Day rainfall at Pohnpei and Consecutive Dry Days at Yap since 1952. The remaining annual, half-year and extreme daily rainfall trends show little change at both sites.

Tropical cyclones (typhoons) affect the Nauru mainly between June and November. An average of 71 cyclones per decade developed within or crossed the Nauru’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) between the 1977 and 2011 seasons. Tropical cyclones were most frequent in El Niño years (88 cyclones per decade) and least frequent in La Niña years (38 cyclones per decade). The neutral season average is 84 cyclones per decade. Thirty-seven of the 212 tropical cyclones (17%) between the 1981 and 2011 seasons became severe events (Category 3 or stronger) in the Nauru’s EEZ. Available data are not suitable for assessing long-term trends.

Wind-waves in the Nauru are dominated by north-easterly trade winds and westerly monsoon winds seasonally, and the El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) inter-annually. There is little variation in wave climate between the eastern and western parts of the country; however Yap, in the west, has a more marked dependence on the El Niño–Southern Oscillation in June–September than Pohnpei, in the east. There is data that is available but are not suitable for assessing long-term trends. For more information see Section 4.3 of the NAURU chapter p67) under Australian Bureau of Meteorology and CSIRO (2014). Climate Variability, Extremes and Change in the Western Tropical Pacific: New Science and Updated Country Reports, Pacific-Australia Climate Change Science and Adaptation Planning Program Technical Report, Australian Bureau of Meteorology and Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, Melbourne, Australia.

For detailed information, go to: Australian Bureau of Meteorology and CSIRO, 2014.

Future climate

For the period to 2100, the latest global climate model (GCM) projections and climate science findings for NAURU indicate:

- El Niño and La Niña events will continue to occur in the future (very high confidence), but there is little consensus on whether these events will change in intensity or frequency;

- Annual mean temperatures and extremely high daily temperatures will continue to rise (very high confidence);

- Average annual rainfall is projected to increase (medium confidence), with more extreme rain events (high confidence);

- Drought frequency is projected to decrease (medium confidence);

- Ocean acidification is expected to continue (very high confidence);

- The risk of coral bleaching will increase in the future (very high confidence);

- Sea level will continue to rise(very high confidence); and

- Wave height is projected to decrease in December–March (low confidence), and waves may be more directed from the south in the June–September (low confidence)

For detailed information, go to: Australian Bureau of Meteorology and CSIRO, 2014.

Date updated: March 2016

Governance

Nauru ratified the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in 1993 and the Kyoto Protocol in 2001. The Government has taken concrete steps to ensure compliance with the obligations under these international conventions. The country’s First National Communication was submitted to the UNFCCC in 1999, and its Second National Communication is under development. Nauru also participates in regional climate change meetings, including of the Pacific Climate Change Roundtable which monitors the implementation of the Pacific Island Framework for Action on Climate Change (PIFACC) providing the overall regional agenda for responding to the challenges of climate change.

In 2014, the Government of Nauru committed to the Small Islands Developing States Conference (SIDS) and actively participated in the development of the post-2015 cooperation framework for the Barbados Program of Action and Mauritius Strategy. Nauru has demonstrated this commitment through their current chairmanship of the Alliance of Small Island Developing States (AOSIS) and their position on the United Nations Open Working Group on the Sustainable Development Goals.

Mainstreaming DRR is an important government commitment, reflected in its endorsement of the Hyogo Framework for Action: 2005-2015 ‘Building the Resilience of Nations and Communities to Disasters’ (HFA) and the Pacific Regional DRM Framework. Adopted by Nauru in 2005, the HFA is a 10-year plan that describes what is required from different sectors and actors to reduce disaster losses. The Pacific Disaster Risk Reduction and Disaster Management Framework for Action 2005 - 2015 (RFA) was endorsed in October 2005. Adapted from the HFA, the RFA reflects an “all hazards” approach to disaster risk reduction and disaster risk management, in support of sustainable development.

As a response to these commitments, Nauru introduced the Disaster Risk Management Act 2008 and in 2010 established the National Disaster Risk Management Office (NDRMO) to coordinate day to day activities. A National Disaster Risk Management Plan was drafted in 2008, but has not been endorsed.

A number of development strategies and policy instruments as a response to climate change have been introduced by the Government therefore since 2005 through the economic reform programme. These include the NSDS 2005-2025 (rev 2009); Nauru’s Utility Sector-A Strategy for Reform; National Energy Policy Framework; National Energy Roadmap 2014-2020; Nauru Utilities Cooperation Act and RONAdapt.

The responsibility for implementing climate change adaptation and disaster risk reduction related activities is shared across different parts of government and the community. However, at the operational level, the Department of Environment under the Ministry of Commerce, Industry and Environment (CIE) has the primary responsibility for coordination, monitoring progress and reporting on the RONAdapt implementation of Nauru’s climate change activities at all government department/sector levels. Strengthening coordination mechanisms such as ensuring ‘coordination policy committees for water, energy and climate change, and waste are effective and functional’ is a medium-term milestones targeted by the NSDS for Nauru to be implemented by 2015 under the Environment strategic area.

The Government of Nauru recognises that effective institutions and the inter-relationships between them are at the heart of its ability to respond to growing climate and disaster risks. For this reason, the Department of Environment under the Ministry of Commerce, Industry and Environment (CIE), Government of Republic of Nauru (GoN) has primary responsibility for coordination of Nauru’s climate change activities. CIE includes a Climate Change Unit as well as a National Disaster Risk Management (NDRM) Unit.

For more information, go to Nauru SNC Report

Date updated: March 2016

National Climate Change Priorities

The National Sustainable Development Strategy (NSDS) is Nauru’s key document to development. The overall impact that the NSDS seeks to make is captured in the peoples vision for development and is stated as “a future where individual, community, business and government partnerships contribute to a sustainable quality of life for all Nauruans”. Following the review of the NSDS in 2009, climate change was included as one of the key elements to be addressed under the ‘Environment’ strategy. It is worth noting the areas that have been ‘significantly strengthened’ also have relevance to effectively addressing climate change in Nauru are:

SDS Areas strengthened in the 2009 review | New strategies and milestones |

|---|---|

Environment |

|

Gender |

|

Community Development |

|

Youth |

|

Law and Justice |

|

Land issues |

|

Fisheries |

|

The NSDS identifies six key priorities or strategies designed to address its ‘Environment’ Strategic Area. While all strategies contribute to achieving adaptation and mitigation efforts to climate change, Nauru specifies two priorities for climate change and includes:

- Develop locally-tailored approaches and initiatives to mitigate the causes of climate change and adapt to its impacts; and

- Enhance resilience to climate change impacts

The Republic of Nauru Framework for Climate Change Adaptation and Disaster Risk Reduction (RONAdapt) – represents the Government of Nauru’s response to the risks to sustainable development posed by climate change and disasters. RONAdapt is intended to support progress towards the country’s national development priorities and the goal of environmental sustainability, by ensuring that a focus on reducing vulnerabilities and risks is incorporated into planning and activities across all sectors of the economy and society. The priorities outlined in the RONAdapt are intended to contribute to the achievement of the National Sustainable Development Strategy (NSDS) and to increasing Nauru’s resilience to climate change and disasters, by targeting the following goals:

- Water security

- Energy security

- Food security

- A healthy environment

- A healthy people

- Productive, secure land resources.

From a disaster perspective, the key water concern in Nauru is drought, and loss of secure water for key services such as the hospital. During periods where there is little or no rain for more than 3 months, Nauru’s water supply situation deteriorates dramatically, and production capacity becomes stressed. If the RO units break down during drought periods, Nauru faces a social and health disaster.

Enhancing water security is therefore both a key national development priority and also fundamental to reducing vulnerability to climate change and to potential disaster events. Under the water sector, there are also some important policy and planning gaps that need to be filled.

Major health issues in Nauru include non-communicable diseases (NCDs) and water-borne illnesses. Nauru has very high rates of NCDs including cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cancer and respiratory diseases.

Nauru’s small population and distance from other countries also presents challenges in providing quality, cost effective health care. Supply lines are not always reliable, key services such as water and energy are at times disrupted, and health infrastructure (including both hospitals) are subject to coastal flooding risks. Lack of local capacity is an additional constraint to improved health outcomes.

Climate change and extreme events are anticipated to introduce additional stresses, both to community health as well as to the functioning of the health care system. There is a need to build local capacity of the health sector to prepare and cope with adverse effects of climate change and vulnerability of disasters.

Food insecurity is a major risk for Nauru, given the island’s dependence on imported foods and its geographic isolation. This situation is also closely linked with health problems such as the prevalence of NCDs, and is exacerbated by government debt and household income levels which make imported foods expensive and supply unsteady. For these reasons, agricultural development is targeted by the NSDS as a priority.

Agricultural production is relatively small at present, and is constrained by limited availability of suitable land and water, and by limited expertise and interest in growing food and raising livestock. The island’s soil is relatively infertile and has poor water holding capacity while in some areas is also contaminated. In addition, the land tenure system means land ownership is fragmented and little is publicly owned, which increases the complexity of land management. What little fertile land remains untouched by mining is in the coastal strip, and thus in small parcels around houses.

Climate change adds to the already significant challenge of attaining the NSDS goal of increasing domestic agricultural production. Despite these constraints, there is potential to increase agriculture production and productivity, and in doing so strengthen food security and improve livelihoods and health, thus contributing to Nauru’s efforts to reduce vulnerability to future climate change.

The Division of Agriculture under department of CIE has primary responsibility for supporting agricultural development from subsistence to small scale farming, and is the lead agency responsible for overseeing implementation of the agriculture sector’s priority CCA and DRR actions. The institutional and human capacity available in Nauru to support and expand agricultural development is limited and needs to be expanded.

Fisheries are a critically important resource in Nauru, contributing to food security and cultural practices (particularly in low income households) as well as providing an important source of foreign revenue for government.

Climate change is also expected to affect fisheries. Nauru lies within the Pacific Equatorial Divergence (PEQD) and the Western Pacific Warm Pool (Warm Pool) provinces, depending on the prevailing El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) conditions. Climate change is projected to increase sea surface temperatures, sea levels, ocean acidification and to change ocean currents. These effects will, in turn, impact on Nauru’s fisheries resources.

The Nauru Fisheries and Marine Resource Management Authority (NFMRA), a statutory corporation under the Nauru Fisheries and Marine Resources Authority Act 1997, is responsible for fisheries management including overseeing, managing and developing the country’s natural marine resources and environment.

The practice of Disaster Management (DM) and Emergency Response (ER) implies strengthening preparedness, response and recovery systems for potential extreme events or disaster scenarios. Oversight of DRM activities lies with the NDRMO (which resides with CIE), supported by high-level guidance from the National Disaster Risk Management Council. Coordination of emergency response is at present the responsibility of the Police department. There are some important policy and planning gaps that need to be filled to strengthen disaster management and emergency response.

The energy sector can play a critical role in helping to improve Nauru’s coping and adaptive capacities with respect to climate change, and to development goals generally. Energy services provide a tool for reducing vulnerability through, for instance, economic empowerment and the delivery of health and education services.

Electricity production is currently reliant on imported diesel, and thus places a significant burden on the government’s limited financial resources. Import-dependency also creates supply risks. Further, energy production is closely linked to water production, since the reverse osmosis desalination units are energy intensive. At the same time, energy infrastructure is located in the coastal strip, and thus susceptible to particular climate and disaster risks which need to be considered in future planning.

From a disaster perspective, a key concern is the potential for outbreak of fire at the tank farm area. The fire protection system at the tank farm is presently not functioning, and is also not of sufficient capacity to extinguish a major fire. Such an event would have major implications for provision of energy to the island, both during the disruption and for quite some time after given limited alternative infrastructure available should the facility be destroyed. The possibility of energy shortages, arising from for instance fuel supply disruptions and/or problems with the power station, is also a critical concern.

The Energy Roadmap endorsed by the government in 2014 sets out strategies and activities in six thematic areas, namely: power, petroleum, renewable energy, demand side energy efficiency, transport, and institutional strengthening and capacity building. Progress implementing the Roadmap will contribute directly towards helping Nauru adapt to climate change and reduce disaster risks. The Energy Roadmap identifies a swathe of institutional strengthening activities for the sector.

Land is a scare resource in Nauru and much of the island has already been degraded by mining activities, which are ongoing. A related issue is that of waste collection, disposal and management. The dump site has very little available capacity, and is being further stressed by the large quantities of waste (mainly plastics) generated by the RPC. Moreover, the existing dump site is not lined, leading to concerns about possible migration of contaminated leachate into Buada lagoon.

At present Nauru has no endorsed land use plan to guide development decisions. Land use planning is critical to, for instance, ensure that future infrastructure investments are coherent with the visions and needs of all of Nauru’s communities. Preparation and endorsement of a Nauru Land Use Plan (broadening the Master Land Use Plan proposed for Topside to focus also on Nauru’s coastal areas) which integrates climate and disaster risks.

As highlighted by the NSDS, strategic infrastructure can play an important role in improving economic productivity and/or reducing community vulnerability, and thus in making Nauru more resilient. The 2011 Nauru Economic Infrastructure Strategy and Investment Plan (NEISIP) identifies the government’s needs and immediate priorities in the infrastructure sector, focusing on short and medium term needs relating to transport, water, sanitation, waste management, telecommunications and government buildings (including schools and hospitals).

Infrastructure needs to be designed and managed with future conditions in mind, sometimes referred to as being “climate proofed” and able to withstand disaster events. Sea level rise and associated coastal erosion, flooding during extreme rainfall events, storm surge and fires are hazards that may threaten vital infrastructure.

The absence of an over-arching coastal zone management plan hinders coordination between government agencies and communities regarding management of the coastal zone. There is also presently no environmental legislation or building codes that govern development activities.

Develop and implement an Integrated Coastal Zone Management Plan (ICZMP), which integrates climate and disaster risks. Over time, this should be integrated as a component of a wider Nauru Land Use Plan.

Protection of scarce land and soil resources is an important issue for reducing environmental degradation and improving the overall health of Nauru’s environmental resources, as is addressing water contamination.

Date updated: March 2016

Adaptation

Nauru established the RONAdapt as part of its national efforts to prepare for adaptation. The RONAdapt represents the Government of Nauru’s response to the risks to climate change and disaster risk reduction and is therefore aligned with the development priorities embedded in the NSDS. It is intended to support achievement of Nauru’s NSDS goals, by highlighting a series of actions that will also reduce Nauru’s vulnerability to climate change and disasters. In doing so, it will improve the country’s social, economic and environmental resilience.

Priority actions are given to those that will work towards the goals in the NSDS, as well as those in sectoral plans and strategies where these already give consideration to climate change and disaster risks. The priorities outlined targets the following goals:

- Water security;

- Energy security;

- Food security;

- A healthy environment;

- A healthy people; and

- Productive, secure land resources

Nauru is keen to improve its resilience which has been severely compromised by nearly a century of intensive phosphate mining. One such improvement will be transition to untapped clean energy sources, such as renewable resources rather than relying on the traditional imported dirty liquid fuels.

The other pressing adaptation strategy is to improve the indigenous food supply and potable water availability and storage. In addition there is a concurrent need to rehabilitate the environment and improve the health of the population.

Nauru’s priority climate change adaptation and disaster risk reduction actions are summarised in thematic areas in the table below (adapted from the SNC Report, 2015):

SECTOR PRIORITY | STRATEGY |

|---|---|

Water |

|

Health |

|

Agriculture |

|

Fisheries and marine Resources |

|

Disaster management and emergency response |

|

Energy |

|

Land management and rehabilitation |

|

Infrastructure and coastal protection

|

|

Biodiversity and environment

|

|

Community development |

|

Education and human development |

|

For detailed information on adaptation actions in Nauru, go to: Nauru SNC report.

Date updated: March 2016

Mitigation

The Government of Nauru realises the difficulties in terms of mitigation and has adaptation to climate change as its top priority. In this respect a transition from relying on imported fossil fuels by putting in place an indigenous solar energy supply is also an adaptation strategy to become more resilient and has as a co-benefit, mitigation.

Nauru’s main mitigation contribution as outlined under the INDC (see section below) is to achieve the outcomes and targets under the National Energy Road Map (NERM), NSDS and recommendations under the SNC and is conditional on receiving adequate funding and resources

The key mitigation intervention is to replace a substantial part of the existing diesel generation with a large scale grid connected solar photovoltaic (PV) system which would assist in reducing the emissions from fossil fuels. Concurrent to the above there needs to be put in place extensive demand side energy management improvements which will complement the PV installation. The demand management improvements are expected to reduce emissions by bringing down diesel consumption further.

The cost of these mitigation measures is likely to be around US$50 million ( US$ 42 million for Solar PV and US$ 8 million for demand side energy efficiency measures) with some uncertainty depending on the storage of energy either as electrical ( battery) or thermal (chilled water) to account for the high night time electrical load on the island. Due to somewhat higher phosphate extraction in past years Nauru’s emissions in 1990 were higher than at present and estimated to be around 80kt. If economic activity proceeds at the current pace the BAU estimate for 2030 emissions of CO2 only will also be around 80kt.

For information on mitigation projects in Nauru, go to "Related Projects" tab.

Intended Nationally Determined Contributions

Nauru’s mitigation contribution will be contingent on obtaining funding and technical assistance to put in place the energy transition and energy savings measures.

Time frame: | 2020-2030 |

|---|---|

Type of Contribution | Conditional Reduction based on identified mitigation actions To replace a substantial part of electricity generation with the existing diesel operated plants with a large scale grid connected solar photovoltaic (PV) system with an estimated cost of 42 million US$ which would assist in reducing the emissions from fossil fuels.

Concurrent to the above there needs to be put in place extensive demand side energy management improvements with an estimated cost of 8 million US$ which will complement the PV installation. The demand management improvements are expected to reduce emissions by bringing down diesel consumption further.

The conditional mitigation contribution discussed above would require a total investment estimated at $50 million USD including substantial technical, capacity building and logistical assistance due to the limited capacity on the island.

Unconditional Reduction

The unconditional contribution includes a secured funding of US$5 million for implementation of a 0.6 MW solar PV system which is expected to assist in unconditional reduction of CO2 emissions marginally. This initiative will be used as a model project for the larger Solar PV plant and in addition assist in terms of technology transfer and institutional learning. |

Type of Reduction | Being a Small Island Development State and a developing country with lowest total emissions in the world, Nauru’s mitigation contributions are non-GHG targets through implementation of conditional and unconditional policies, measures and actions. Nauru also recognizes that mitigation contributions from developed countries may be absolute economy-wide emissions reduction targets relative to a base year while the developing countries can communicate policies, measures and actions departing from business as usual emissions. |

Sectors | Sectoral (energy sector) commitment focussed on a transition to renewable energy in the electricity generation sector and energy efficiency through demand side management. |

Gases | Carbon Dioxide (CO2) |

BAU Emissions | The expected trajectory in emissions is highly uncertain due to paucity of reliable data and uncertainties in economic activities on the island. Contributing factors include both the small size of the economy and the uncertainty of phosphate extraction opportunities and the other recently commenced activities including offshore banking and housing Australian bound refugees. An extrapolation of trends in the last three years suggests economic growth of around 2.2% p.a. Of concern are high levels of expansion in the electricity sector with growth over the same period being around 13% p.a. Estimates, however, are that CO2emissions will increase from 57 kt p.a. in 2014 to close to 80 kt p.a. in 2030. The mitigation options are envisaged to assist in reducing CO2 emission levels by 2030. It is important to note that the BAU emission estimates are not accurate due to substantial gaps in data for the sectors. |

Methodology | The baseline, BAU and mitigation scenario assessments was done using best available historical data entered into the GACMO model which uses IPCC 2006 guidelines and conversion factors. Where data was not available default factors in the software were used. |

Planning Process | Nauru’s INDC originates from a series of strategies, policies and assessments concerned with sustainability, environmental protection and energy supply developed or commissioned by the Government over the past decade. These include: National Sustainable Development Strategy (NSDS) 2005 – 2025 (revised in 2009), The Nauru Energy Road Map 2014-2020 and The Second National Communication (SNC) to the UNFCCC (submitted in 2015). Further, Extensive consultations with all relevant stakeholders were held during the preparation of Nauru’s INDC. |

Fairness, Equity and Ambition | Although a very small nation with absolute levels ofCO2eq emissions under 0.0002 % of world emissions(2014), Nauru wishes to play its part in the enormous challenge presented to the world by threat of global warming. In Nauru’s case the threat is to its very existence.

Nauru is also faced with serious economic challenges. Its once thriving phosphate industry has ceased operation thus depriving Nauru of its major lifeline revenue source. The local infrastructure, including power generation, drinking water and health services, has been adversely affected in recent years by the decline in income from phosphate mining. With fewer prospects in the phosphate industry, Nauru has to look at other alternative revenue sources to support its economic development. Unfortunately, for a country of the size of Nauru (21 km2) with its limited natural resources, the options are not many.

The global goal underlying the assessment of mitigation contribution is to reduce fossil fuel imports by using indigenous renewable energy and implementing energy efficiency measures. In light of the above, for such a remote island already severely damaged by phosphate mining, Nauru’s mitigation contribution is quite ambitious. With regards to equity Nauru cannot be expected to mitigate out of its own resources and would need extensive international assistance. |

Loss and Damage

The issue of loss and damage is important to Nauru, particularly when considering the current low level of mitigation ambition internationally and the science is telling us that there will be limits to adaptation. Nauru supports the concept that loss and damage must be considered as a separate and distinct element from adaptation in the 2015 COP21 agreement.

The inclusion of loss and damage in the INDC is twofold. First, its purpose is to highlight the significance of the issue for Nauru and second, to present our views on loss and damage in the 2015 climate agreement.

The reality of the impacts of climate change that Nauru and Small Island Developing States (SIDS) are already experiencing means adaptation is absolutely critical. However, the science is telling us that we are quickly moving towards a reality where adapting will not be sufficient. The prospect for loss and damage associated with climate change for Nauru and SIDS are real. The IPCC findings in both the Fourth and Fifth Assessment Report from Working Group II show that there are substantial limits and barriers to adaptation. In Warsaw, Parties also acknowledged that loss and damage associated with the adverse effects of climate change involves more than that which can be reduced by adaptation..

Nauru calls for loss and damage to be included as a separate element of the 2015 agreement, one that is separate and distinct from adaptation. Loss and damage must be addressed in a robust, consistent and sustained manner. This can only be accomplished through a loss and damage mechanism that is anchored in the 2015 agreement. Anchoring the mechanism in the 2015 agreement will ensure that it is permanent.

Nauru acknowledges that there is on-going work under the Warsaw International Mechanism on Loss and Damage, including a 2016 Review.

Immediate and adequate financial, technical and capacity building support for loss and damage is needed and to be provided on a timely basis for Nauru and other SIDS to address loss and damage. It is beyond our current national means to address loss and damage from climate change and financial flows from developed countries for addressing loss and damage in Nauru and other vulnerable developing countries should be new and additional to financing for those for mitigation and adaptation.

For more information, go to Nauru INDC.

Date updated: March 2016

Knowledge Management & Education

Nauru is making various efforts and prioritising both climate change mitigation and adaptation as one of the core development issues. To address the capacity building issues, Nauru in association with various development partners has been conducting many short term capacity development training programs and workshops for the policy makers, government and non-government staffs, students and local population. Both government and non-government institutions in Nauru have effectively stimulated interest and understanding of environmental issues through workshops, quiz contests, role-plays, theatre, radio, TV and Video shows.

Government of Nauru is seeking financial and infrastructure support to expand the capacity building and awareness raising at various levels. There are barriers in dissemination of the right information to the right target audience, alongside complications that can arise when specialised English terminology is used during consultation and awareness programmes. The key issues, barriers and opportunities are discussed below:

- The capacity building and public awareness program and activities need to be focused and relevant in the local context. Efforts should be focussed on making climate-change information available to a wider audience.

- Topics related to global climate change needs to be incorporated in the curricula of primary and secondary schools and appropriate training of teachers in environmental education.

- Provide incentives to the students for choosing higher education in environment, climate change and related development studies.

- Provide support for environment and climate change higher education.

- Start established institution for climate change & sustainable development

- Creating easy access to climate change information and make this information available in local languages

- Periodic assessment of impact and effectiveness of current awareness programmes should be undertaken.

For more information go to: SNC REPORT TO UNFCCC Portal.

Date updated: March 2016

References

List of references used to develop country profile:

- Australian Bureau of Meteorology and CSIRO (2014). Climate Variability, Extremes and Change in the Western Tropical Pacific: New Science and Updated Country Reports. Pacific-Australia Climate Change Science and Adaptation Planning Program Technical Report, Australian Bureau of Meteorology and Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, Melbourne, Australia

- Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific, United Nations, July 2007.

- Pacific Disaster Net

- Forum Secretariat website

- Pacific Climate Change Portal Project Database

- Nauru Second National Communication Report to the UNFCCC

- Nauru INDC

Date updated: March 2016