Ms. Isabela Silk

Secretary, Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade

PO Box 1349

Majuro, Republic of Marshall Islands

Telephone: (692) 625-318

Email: [email protected]

Ms. Moriana Phillips

General Manager

RMI Environment Protection Agency

Email: [email protected]

Mr Clarence Samuel

Director, Climate Change Directorate, Ministry of Environment (CCD)

Policy Coordination (OEPPC)

Email: [email protected]

P.O. Box 975 Delap, Majuro - 96960

Marshall Islands

Tel: + 692 625-7944/7945

Mr. Warwick Harris

Deputy Director, Office of Environment Planning & Policy Coordination (OEPPC)

Government of Marshall Islands

PO Box 975

Majuro, Republic of Marshall Islands

Telephone: (692) 625 7944/5

Fax: (692) 625 7918

Email: [email protected]

Mr. Reginald White

Director and Meteorologist in Charge

Government of Marshall Islands

Email: [email protected]

Date updated: April 2024

Country Overview

Capital: Majuro

Land: 181 sq km

EEZ: 2.1 million sq km

Population: 54,000 (2003 est.)

Language: English, Marshallese

Currency: United States Dollar

Economy: Agriculture and US Military spending

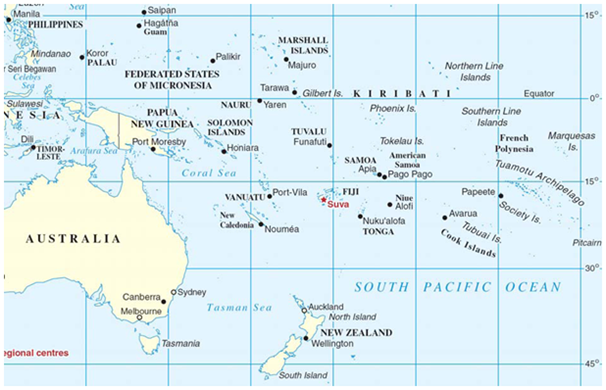

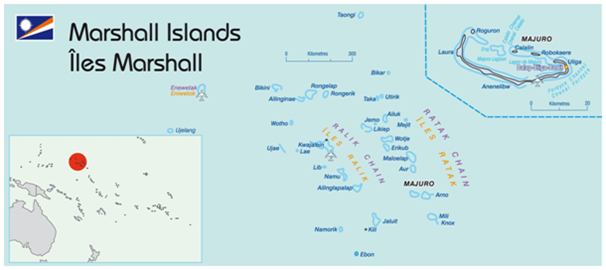

The Republic of the Marshall Islands (RMI) is a Small Island Developing State and home to nearly 70,000 people. It is a raised atoll island nation located in the North Pacific Ocean at equal distance between Hawaii and Australia. The country comprises 34 major islands and atolls, including the atolls Bikini, Enewetak, Majuro, Rongelap, and Utirik. Approximately 1,225 low-lying islets make up the twenty-nine atolls of the Marshall Islands. The islands are scattered in an archipelago consisting of two rough parallel groups, the eastern ‘Ratak’ (sunrise) chain and the western ‘Ralik’ (sunset) chain. However, for climate analysis a difference is made between the North and South Marshall Islands. an average elevation of 2 metres, RMI is uniquely vulnerable to the impacts of climate change.

Twenty-two of the atolls and four islands are inhabited, and almost 70% of the population live on Kwagelin (Ebeye) and Majuro, the RMI capital. Bikini and Enewetak are former US nuclear test sites; Kwajalein, the famous World War II battleground, surrounds the world's largest lagoon and is used as a US missile test range. The Marshall Islands have also claimed the Wake Islands (Enenkeo) to the north, currently an American possession and not occupied by Marshallese in historic times.

The topography of the islets is low and flat, with maximum natural elevation rarely exceeding 3m’ The highest recorded point on the atoll, Likiep, is 10m above sea level. Soils are nutrient-poor and subject to salt spray, and hence the vegetation type is very limited.

Spanish, German, Japanese and Americans have been part of the colonial history. In July 1977, the Marshall Islands voted in favour of separation from the U.S Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands and in May 1979, it declared self-government under its own constitution. In March 1982, the Marshall Islands declared itself a Republic and in September 1991, the RMI became a member of the United Nations.

The legislative branch of government consists of the Nitijela (Parliament). The Nitijela has 33 members from 24 districts elected for 4-year terms. Members are called Senators. The Executive comprises the President and the Cabinet. The President is elected by majority vote from the membership of the Nitijela and then selects the Cabinet (currently 10 ministers plus the President) from members of the Nitijela. There are four Court systems comprising of a Supreme Court and a High Court plus district and community courts and the traditional rights court. The 13-member Council of Chiefs (Iroij) serves a largely consultative function on matters of custom and traditional practice.

Economic Summary

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) 2009: US$152.8 million

GDP per capita (2009): US$2,504

GDP real growth (2008): 1.5%

Unemployment (2008): 30.9%

Government is the largest employer, employing 46% of the salaried work force. The Marshall Islands is still mainly a copra-based subsistence economy. Copra and coconut oil constitute 90% of exports. Yellowfin tuna are exported fresh for the Japanese sushi market. The tourism industry now employs 10% of the labour force. There is a chronic trade imbalance in favour of the United States and Japan, and newer partners include Australia and Republic of China/Taiwan..

Majuro and Ebeye have service-oriented economies sustained by government expenditure and the US Army installation at Kwajalein Atoll. The airfield in Ebeye also serves as a second national hub for international flights. RMI has a significant international shipping registry under which large numbers of ships owned by foreign entities are registered in its national shipping registry and fly its flag.

Economic potential lies in marine resources and seabed mineral deposits. The Marshall Islands has a 2.1 million km2 Exclusive Economic Zone rich in skipjack and yellowfin tuna. The Asian Development Bank has undertaken an assessment of RMI’s fish resources.

Transport issues are often cited as a constraint to economic growth. Currently, the main air service is provided by United Airlines and includes Kwajalein and Majuro as stopovers on the 'Circle Micronesia' island-hopper route between Honolulu and Guam. Flights travel west to east and east to west on alternate days.

Based on a 2012 International Monetary Fund (IMF) report after a 5½ percent expansion of the economy in FY2010, helped by an expanding fishery sector, growth fell sharply to 0.8 percent in FY2011, as a result of high commodity prices, labor shortages, and delay in the airport renovation project due to disagreement on the environment protection standard to be applied. Inflation remained elevated at 5½ percent in FY2011, reflecting high commodity prices. The economy is heavily dependent on foreign grants which fund a large public sector, but are subject to scheduled declines.. The weak financial position of some public enterprises could hinder economic activities and erode public finances. Fluctuations in fuel and food prices would also pose a substantial risk given the RMI’s high dependence on commodity imports.

Financial Management

RMI’s Public Expenditure and Financial Accountability (PEFA) assessment and initial public finance management (PFM) consultations have recently been completed, as well as a peer review of their national sustainable development planning and budgeting. These processes provide a detailed analysis of RMI’s PFM, and now publically available (can inform climate change finance options including direct budget support currently the subject of a consultancy being prepared with the support of SPC - GCCA:PSIS. Based on the IMFand RMI Peer Review reports (2012), achieving long-term budgetary self-reliance and sustained growth remains a challenge. Under the baseline projection, sluggish growth and fiscal adjustment imply a large projected revenue shortfall in 2023 when Compact grants are set to expire. Closing this revenue gap would require a fiscal adjustment of around 4% of GDP over the medium term.Comprehensive public sector and structural reforms would be required to achieve this adjustment. These depend on ongoing efforts to unlock private sector growth. These include: (i) implementation of tax reform; (ii) targeted expenditure cuts; (iii) accelerated reforms of the state-owned enterprises (SOEs); and (iv)removal of obstacles to private sector development. At the same time external finance coordination, high level endorsed medium term budget planning, and a single simplified system for reporting across sectors are recommended by the Peer Review, along with other steps such as oversight of the development banks suggested by the IMF.

Aid Management and Budget Support

GDP is derived mainly from Compact transfer payments from the United States. In 2010, direct US aid accounted for 61.3% of the Marshall Islands' fiscal budget. Since the end of World War II, the RMI has retained close social, economic and political ties with the US. Since 1986, this relationship has been formalized in the form of the two subsequent Compacts of Free Association, outlining US assistance and diplomatic ties to the RMI.

The 2003 amended Compact of Free Association, followed two years of intensive negotiations jointly by the RMI and the FSM to renew the fiscal and strategic relationship. As a result of the amended Compact that entered into force in 2004, the US government has agreed to provide RMI and the FSM jointly some US$3.5 billion in economic and service aid over the next 20 years. The US retains the right to maintain a military missile testing base on Kwajalein, while RMI citizens have free access to the US and certain education, health and welfare services and federal funding until 2023.

The Compact is designed to wean RMI away from US support over the course of the 20 years. The aid formula is for decreasing US assistance and increasing emphasis on private sector and foreign investment. The large amount of financial assistance provided under the Compacts has enabled the national government to provide numerous public and other services resulting in public sector and public enterprise expenditures dominating and driving economic growth in direct competition with the private sector. Consequentially, there has been little real growth in the private sector.

The RMI government is also highly dependent on other external sources of assistance, particularly from the Asian Development Bank (ADB), Republic of China (ROC) and to a lesser extent, Japan. Most of the assistance from these sources takes the form of technical assistance loans and grants (ADB), funding of infrastructure development projects (Japan), and supplementation of the national budget (ROC). The dependence of the RMI government on external funding assistance from the USA and other countries poses significant issues regarding the sustainability of national development efforts. The challenge RMI faces is how to coordinate external donor priorities and agendas along with its own national priorities and initiatives.

Since its independence, RMI has been heavily reliant on external assistance, with grants averaging 60% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP). International support will remain important as RMI fulfils its National Strategic Development Plan: Vision 2018 (NSP). The NSP provides a general framework for sustainable development, and contains linkages to climate change and disaster risk management through its goal of environmental sustainability. It is a guide for development and progress in the medium term, through a three-year rolling plan, and will be updated continually for use in meeting longer-term objectives as RMI moves towards the scheduled completion of funding under “The Compact of Free Association, as Amended” in 2023.

Source: ©SPC, 2013.

Date updated: March 2016

Current Climate

The warming trends are evident in both annual and half-year mean air temperatures at Majuro (southern Marshall Islands) since 1955 and at Kwajalein (northern Marshall Islands) since 1952. The frequency of Warm Days has increased while the number of Cool Nights has decreased at both Majuro and Kwajalein. These temperature trends are consistent with global warming. At Majuro, a decreasing trend in annual rainfall is evident since 1954. This implies either a shift in the mean location of the Inter-Tropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) away from Majuro and/or a change in the intensity of rainfall associated with the ITCZ. There has also been a decrease in the number of Very Wet Days since 1953. The remaining annual, seasonal and extreme rainfall trends at Majuro and Kwajalein show little change.

Tropical cyclones (typhoons) affect the Marshall Islands mainly between June and November. An average of 22 cyclones per decade developed within or crossed the Marshall Islands Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) between the 1977 and 2011 seasons. Tropical cyclones were most frequent in El Niño years (50 cyclones per decade) and least frequent in La Niña years (3 cyclones per decade). Thirteen of the 71 tropical cyclones (18%) between the 1981/82 and 2010/11 seasons became severe events (Category 3 or stronger) in the Marshall Islands EEZ. Available data are not suitable for assessing long-term trends.

Wind-waves in the Marshall Islands are influenced by trade winds seasonally, and the El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) interannually. Wave heights are greater in December–March than June–September.

Source: Australian Bureau of Meteorology and CSIRO, 2014.

Future Climate

For the period to 2100, the latest global climate model (GCM) projections and climate science findings indicate:

- El Niño and La Niña events will continue to occur in the future (very high confidence), but there is little consensus on whether these events will change in intensity or frequency;

- Annual mean temperatures and extremely high daily temperatures will continue to rise (very high confidence);

- Average rainfall is projected to increase (high confidence), along with more extreme rain events(high confidence);

- Droughts are projected to decline in frequency (medium confidence);

- Ocean acidification is expected to continue (very high confidence);

- The risk of coral bleaching will increase in the future (very high confidence);

- Sea level will continue to rise(very high confidence); and

- Wave height is projected to decrease in the dry season (low confidence)and wave direction may become more variable in the wet season (low confidence)

Source: Australian Bureau of Meteorology and CSIRO, 2014.

Date updated: March 2016

Governance

The Government charted the Vision 2018 as the first segment of the Government’s Strategic Development Plan Framework 2003-2018. It provides a sound basis for future economic resource and self-sufficiency including sustainable growth in consistent with the Sustainable and Millennium Development Goals and now the S.A.M.O.A Pathway. Vision 2018 was developed through an extensive consultative process starting with the Second National Economic and Social Summit, and followed by extended deliberations by various Working Committees established by the Cabinet. The second and third segments of the Strategic Development Plan consist of Master Plans focusing on major policy areas, and the Action Plans of Ministries and Statutory Agencies. These documents show programs and projects together with the appropriate costing.

The national priorities set out in the government’s Strategic Development Plan Framework 2003–2018 (SDP) are an integrated set of policies in the areas of:

- Macroeconomic and human resources development;

- Development of productive sectors;

- Outer Islands development;

- Science and technology; and

- Culture and traditions

These policies address key cross-sectoral issues, including the environment.

In 2011, the RMI government adopted the National Climate Change Policy Framework (NCCPF), which sets out RMI’s commitments and responsibilities to address climate change. The NCCPF recognizes that climate change exacerbates already existing development pressures. These pressures arise from extremely high population densities (on Ebeye and Majuro in particular), rising incidences of poverty, a dispersed geography of atolls over a large ocean area (making communication difficult and transport expensive), and a small island economy that is physically isolated from world markets but highly susceptible to global influences. Environmental pressures are also acute, with low elevation, fragile island ecosystems, a limited resource base and limited fresh water resources (exacerbating the reliance on imports) resulting in an environment that is highly vulnerable to overuse and degradation.

The NCCPF policy framework is intended to guide the development of adaptation and energy security measures that respond to RMI’s needs with an “All Islands Approach”, foster an environment in which the RMI can be better prepared to manage the current and future impacts of climate change while ensuring sustainable development, and provide a blueprint for building resilience in partnership with regional and global partners.

RMI developed an innovative Joint National Action Plan (JNAP) for Climate Change Adaptation and Disaster Risk Management National Action Plan (DRM NAP) that sets out actions to adapt against the effects of climate change and respond effectively to natural disasters. The JNAP Matrix aligns with actions identified under the RMI National Action Plan for Disaster Risk Management 2008-2018 and the aforementioned NCCPF. The JNAP’s strategic goals are:

- Establish and support an enabling environment for improved coordination of disaster risk management /climate change adaptation in the Marshall Islands;

- Public education and awareness of effective CCA and DRM from the local to national level;

- Enhanced emergency preparedness and response at all levels;

- Improved energy security, working towards a low carbon emission future;

- Enhanced local livelihoods and community resilience for all Marshallese people; and

- Integrated approach to development planning, including consideration of climate change and disaster risks.

The Office of Environmental Planning and Policy Coordination (OEPPC) is the national operational climate change focal point for RMI. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs as the political focal point for all climate and disaster related matters of national concern. OEPPC acts as the chair and secretariat to the National Climate Change Committee (NCCC) established as part of rolling out activities of the 2011 National Climate Change Policy Framework.

The NCCC consists of both government, non-government organizations and have developed and launched a number of key documents at the national level. The National Climate Change Committee comprises the Secretaries of the following RMI government agencies:

- Chief Secretary- Chairman

- Office of Environmental Planning and Policy Coordination (OEPPC)

- Ministry of Resources & Development (R&D)

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MoFA)

- Marshall Islands Marine Resources Authority (MIMRA)

- Environment Protection Agency (RMIEPA)

- Ministry of Finance (MoF)

- Ministry of Health (MoH)

- Ministry of Education

They include relevant NGOs in particular WUTMI, MICNGOs and the Marshall Islands Conservation Society and Community Based Organizations.

In 2014, through the works of the NCCC, the government endorsed a Joint Disaster Risk Management (DRM) and Climate Change National Action Plan (JNAP) and a Climate Change Policy 2014, as a means to implement the CC policy and give renewed interest in actions that were initially identified under the DRM NAP.

Climate change activities are in line with the NCCPF vision of “Building the resilience of the people of the Marshall Islands to climate change”. Efforts to address climate-related impacts include public awareness-raising, participation in regional climate change adaptation projects (addressing capacity building as well as developing strategies for food and water security) and renewable energy strategies.

Although the Government has endorsed the NCCPF and DRM NAP, the JNAP remains to be explicitly adopted by Government for implementation. There also remains limited capacity to undertake DRR/DRM activities both from a human resources and financial perspective. While Local Governments for Majuro and Ebeye have disaster risk reduction plans in place, outside of the more urbanized areas, disaster risk management has been primarily reactive than proactive. According to the National Progress Report on Implementation of the Hyogo Framework 2011-2013, “Strengthened capacity, through appropriately resourced focal points in relevant offices, is needed at the national level to ensure the JNAP, as the key policy document for DRR/DRM and climate change, is implemented across all sectors.”

The Ministry of Internal Affairs (MoIA) is becoming more proactive and better recognized as a key link between national and local levels particularly for DRR/DRM issues. Annual Mayors Conferences and Mobile Teams, organized through MoIA, allow for the communication of important issues (including DRR/DRM and climate change issues) between the national and local levels. Drought relief efforts following the May 2013 Presidential Declaration of Disaster across 14 northern atolls have allowed the Government and development partners to enact what appears to be highly effective disaster relief protocols, though this is ongoing and too recent for closer analysis in this report.

Date updated: March 2016

National Climate Change Priorities

Building the resilience of the people of RMI to climate change is informed by the principles of sustainable development as outlined by the Vision 2018. The RMI is incorporating climate change in every aspect of its economy and every sustainable development and planning decision made must address climate change. For example, coastal developments must take into consideration sea level rise, while agricultural policies must recognise the need for new types of cultivars to withstand drought and saline soil and water conditions.

Based on existing national policies and plans, and from related and recent consultations, the following areas were identified as priorities to be addressed in order to mainstream climate change considerations will be mainstreamed into the following national priority areas:

- Strengthen the Enabling Environment for Climate Change Adaptation and Mitigation, including Sustainable Financing

- Adaptation and Reducing Risks for a Climate Resilient Future

- Energy Security and Low-Carbon Future

- Disaster Preparedness, Response and Recovery

- Building Education and Awareness, Community Mobilization, whilst being mindful of Culture, Gender and Youth

These are the priority areas that underpin sustainable development in RMI. Mainstreaming climate change into these priority areas build the overall resiliency of the people of RMI. To address climate change risks in each of the priority areas, five strategic goals will provide a pathway to an integrated, whole of Marshall Islands response:

- Food and Water Security

- Energy Security and Conservation

- Biodiversity and Ecosystem Management

- Human Resources Development, Education and Awareness

- Health

- Urban Planning and Infrastructure Development

- Disaster Risk Management

- Land and Coastal Management, including Land Tenure

- Transport and Communication

Each of the five strategic goals is accompanied by objectives and outcomes. These are both informed by, and will contribute to the achievement of, Vision 2018

For more information, go to: https://www.sprep.org/attachments/Climate_Change/RMI_NCCP.pdf

Date updated: March 2016

Adaptation

RMI’s people are among the most vulnerable in the world to the impacts of climate change. Many of these impacts are already occurring, inflicting damage and imposing substantial costs on the Marshallese government and people – costs that will only increase in the coming years.

RMI is committed to the strongest possible efforts in safeguarding security and human rights, as well as advancing development aspirations, in light of projected climate impacts and risks. RMI has no choice but to implement urgent measures to build resilience, improve disaster risk preparedness and response, and adapt to the increasingly serious adverse impacts of climate change. RMI commits to further developing and enhancing the existing adaptation framework to build upon integrated disaster risk management strategies, including through development and implement of a national adaptation plan (and further integration into strategic development planning tools), protecting traditional culture and ecosystem resources, ensuring climate-resilient public infrastructure and pursuing facilitative, stakeholder-driven methods to increase resiliency of privately-owned structures and resources. RMI seeks to consider, as appropriate, the legal and regulatory means to best support these approaches.

RMI considers that adaptation action will have mitigation co-benefits, with efforts such as mangrove and agriculture rehabilitation programs likely to enhance carbon sinks as well as assist with protection of water resources and the health of the RMI people.

The JNAP priorities outlined above set outs the adaptation priorities or goals of RMI to adapt to the adverse impacts of climate change.

Water security is one the priority development areas that is urgently in need of adaptation strategies and resources due to experiences of drought and post-disaster. As a result, the National Water and Sanitation Policy developed with this in mind. It aims to provide broad guidelines and support the state organ, including its central and local governments, in the formulation of water and sanitation laws, guidelines, strategies, investment plans, programs and projects. These considered as adaptation priorities are:

- Provide guidance and define rules and responsibilities for water and sanitation investment and activities for all sector stakeholders;

- Provide a framework for the management of freshwater resources, water supply, safe disposal of excreta and wastewater; and the promotion of hygienic behaviors; and

- Cover all people, organizations and areas throughout RMI.

The objectives of the Water and Sanitation Policy are to:

- Reduce the occurrence of waterborne illness;

- Ensure water resource sustainability;

- Ensure utilities are financially solvent;

- Target services and improvements at the disadvantaged;

- Be resilient to climate variability and extreme events.

RMI completed piloting a number of adaptation measures in response to drought as one of the climate hazards to have impacted the country in recent times. As of January 2016, RMI is suffering drought as a result of El Nino. In a response to reduce the impacts of drought in the islands, RMI had piloted work in improving the catchment and reservoir system on the main island of Majuro. The island uses its largest paved area – the airport runway – to collect rainwater, and then diverts it to a series of storage tanks where it is treated and piped to communities. The increasing population and outdated infrastructure, compounded by unpredictable and challenging weather, meant that the system was becoming inadequate. RMI’s response was to repair the reservoir, including relining the tanks and installing a cover to reduce evaporation. The renovated reservoir was officially opened on 2 April 2014. The reservoir is now able to hold up to 36.5 million gallons, compared with 31.5 million gallons prior to the improvements. The higher capacity means greater water security for the people of Majuro. For more information about this particular response, go to: www. https://www.sprep.org/pacc/marshallislands

For more information, go to: http://biormi.org/oeppc/

Date updated: March 2016

Mitigation

Though RMI’s total greenhouse gas emissions are negligible on a global scale, the country takes its national motto, “Jepilpilin ke ejukaan" (“Accomplishment through joint effort”), very much to heart. RMI recognizes that it has a role to play in the global effort to combat climate change, demonstrating that even with its limited means it will undertake the most ambitious action possible.

Current Status

The estimated sectoral mix of RMI’s anthropogenic GHG emissions (CO2-e), as calculated for 2010 in the forthcoming Second National Communication, is as follows: electricity generation (~54%), land and sea transport (~12%),waste (~23%), and other sectors (~11%).

Almost 90% of national energy needs are currently satisfied by imported petroleum products, although biomass remains important for cooking and crop drying on outer islands.

All CO2 emissions are the result of combustion of imported fossil fuels in five sectors:

- Electricity generation;

- Sea transport;

- Land transport;

- Kerosene for lighting on outer islands; and

- LPG, butane and kerosene for cooking.

Like other island nations in the Pacific, RMI suffers from high and volatile fuel prices, while lacking any known fossil fuel reserves of its own. Following a major fuel price spike in July 2008, the RMI Government declared a state of economic emergency. This quickly drew national attention to the need to reduce the reliance on imported fossil fuels, and to scale-up renewable energy as a replacement. Prior to 2008, the emphasis had been mainly on small-scale solar for the households of the outer islands. However, since 2008, there has been a rapid expansion of solar investment to add renewable energy generation to the existing diesel-powered grids on the urban islands.

This, along with the introduction of supply-side efficiency measures by the Marshalls Energy Company (MEC) and demand-side load reductions, has led to a recent decline in fuel oil usage for electricity generation. The vision for the proposed 2014 National Energy Policy (NEP) is “an improved quality of life for the people of the Marshall Islands through clean, reliable, affordable, accessible, environmentally appropriate and sustainable.

Planned Actions

In preparing its INDC, RMI considered various scenarios for the potential contribution of renewable energy and energy efficiency initiatives in the power generation and transport sectors, as well as the potential role of measures to reduce emissions from the waste, cooking and lighting sectors.

As currently estimated, progress towards achieving RMI’s targets would entail reducing emissions from: the electricity generation sector by 55% in 2025, and 66% in 2030; transportation (including domestic shipping) by 16% in 2025 and 27% in 2030; waste by 20% by 2030; and 15% from other sectors (cooking and lighting) by 2030.

Specific areas of action contemplated to make progress towards the INDC targets include:

- Ground and roof mounted solar with associated energy storage;

- Ongoing demand-side energy efficiency improvements (e.g. prepayment meters, end user efficiency improvements);

- Supply-side energy efficiency improvements (e.g. new engines and system upgrades, heat recovery from engines);

- Small scale wind-powered electricity generation;

- Replanting and expansion of coconut oil production for use in electricity and transport sectors blended with diesel;

- Vehicle inspections and maintenance;

- Introduction of electric vehicles, and emission standards for current vehicles;

- Introduction of solar-charged electric lagoon transport;

- Reduction in methane production in landfills through pre-sorting of waste and entrapment of methane;

- Transition to electric and solar cook stoves from LPG cook stoves;

- Reduction of kerosene for lighting in outer atolls; and

- Additional GHG reductions may become possible through the use of new technologies allowing the extraction of ocean energy for power generation.

Many of these actions will depend on the availability of the necessary finance and technology support, as described in the section on “Support for Implementation.”

Efforts to overachieve

RMI will undertake the strongest possible efforts to achieve and, where possible, overperform on the commitment in its INDC. For example, should potential plans and specific pathways for deployment of OTEC be clarified, and should practical, island-driven application be proven, this would have the potential to allow RMI to substantially over-perform on its present commitment. Further, should additional technological developments occur, and cost barriers be reduced, further progress could be possible in all relevant sectors, including energy generation and transportation. RMI looks forward to the opportunity to consider the possible deepening of its emission reduction trajectory when it seeks to update its mitigation commitment in five years’ time.

Intended Nationally Determined Contributions

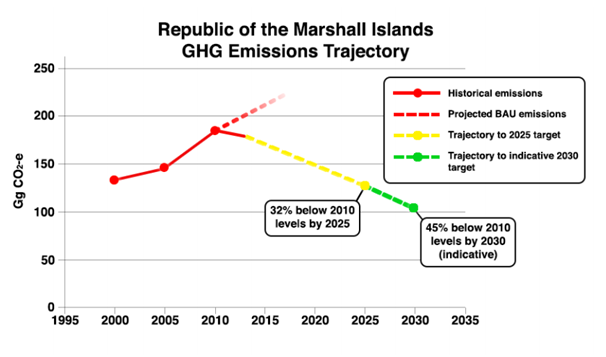

RMI’s commits to a quantified economy-wide target to reduce its emissions of greenhouse gases (GHG) to 32% below 2010 levels by 2025. RMI communicates, as an indicative target, its intention to reduce its emissions of GHGs to 45% below 2010 levels by 2030. Period of Implementation: Start year: 2020, End year: 2025 |

These targets progress beyond RMI’s Copenhagen pledge, and are based on the more rigorous data in RMI’s forthcoming Second National Communication. They put RMI on a trajectory to nearly halve GHG emissions between 2010 and 2030, with a view to achieving net zero GHG emissions by 2050, or earlier if possible. This will require a significant improvement in energy efficiency and uptake of renewables, in particular solar and biofuels, as well as transformational technology, such as Ocean Thermal Energy Conversion (OTEC).

Type and level of commitment: Absolute economy-wide emission reduction target (excluding LULUCF)

Reference year or period: 2010 base year (~185 Gg CO2-e)

Estimated quantified emissions impact:

Commitment to reduce GHG emissions by 32% below 2010 levels by 2025

Indicative target to reduce GHG emissions by 45% below 2010 levels by 2030

Coverage | % of national emissions | ~100% |

Sectors |

[Note: emissions from sectors not listed are negligible] | |

Gases | Carbon dioxide (CO2) Methane (CH4) Nitrous Oxide (N2O) [Note: emissions of GHGs not listed are negligible] | |

Geography | Whole country | |

Further information, relevant to commitment type | N/A | |

Intention to use market based mechanisms to meet commitments

| No | |

Land sector accounting approach

| N/A | |

Estimated macro-economic impact and marginal cost of abatement

| N/A | |

Metrics and methodology

| Consistent with methodologies used in RMI’s forthcoming Second National Communication (1996 IPCC Guidelines). | |

Planning process | RMI’s INDC was developed through an all-inclusive process of engaging relevant stakeholders in and outside government, including the country’s first National Climate Change Dialogue and three rounds of stakeholder consultations. This process has produced genuine national ownership of the INDC and highlighted synergies with other UNFCCC-related processes, including National Communications, Biennial Update Reports, National Adaptation Planning, and Nationally Appropriate Mitigation Actions (NAMAs) | |

Fair and ambitious | RMI’s emissions are negligible in the global context (<0.00001% of global emissions). According to data reflected in RMI’s forthcoming Second National Communication, RMI’s emissions peaked around 2009 and have been trending downwards since, in line with the goals in the National Energy Plan and National Climate Change Policy, based on the ‘National Climate Change Roadmap’ (2008). Given its low GDP per capita (approx. USD3,6001), extreme vulnerability and dependence on external support, RMI’s proposed targets are ambitious compared to those proposed by other countries and measured against any objective indicators. They put RMI on a trajectory to nearly halve GHG emissions between 2010 and 2030, with a view to achieving net zero GHG emissions by 2050, or earlier if possible. RMI’s pursuit of an absolute, economy-wide emission reduction target is a far more ambitious approach than the contemplation in Decision 1/CP.20 that “LDCs and SIDS may communicate information on strategies, plans and actions for low GHG emission development…” (para. 11) | |

For more information, go to: http://www4.unfccc.int/submissions/INDC/Published%20Documents/Marshall%20Islands/1/150721%20RMI%20INDC%20JULY%202015%20FINAL%20SUBMITTED.pdf

Date updated: March 2016

Knowledge Management & Education

RMI acknowledges knowledge management and education under the NCCFP Goal 5 “Education and Awareness, Community Mobilization, whilst being mindful of Culture, Gender and Youth”. The outcomes are coordinated by OEPPC as the secretariat for the NCCC and through the Chief Secretary and Minister assisting the President. Collaboration, consultations and coordination of implementation activities with other line Ministries and agencies have been on-going and OEPPC is a member to most of the national committees such as the Water Taskforce Committee, National Climate Change Committee (NC3), Food Security Committee and Coastal & Marine Advisory Council (CMAC).

The policy framework notes that ‘education, awareness and community mobilization, and appropriate considerations of culture, gender and youth are crucial to underpin the climate change policy’ and is ‘critical in ensuring a shift from a business as usual approach to doing business with climate change and disaster risks in mind’.

While knowledge management and mainstreaming climate change into curricula are not specifically goals, the most relevant objective (objective 5.2) is ‘To mobilise public interest and engagement on the subject of climate change including youth groups ...’. The expected outcome is ‘increased discourse on climate change in planning for sustainable development at national, local government and community levels.’

Source: Government of Marshall Islands, 2011.

Date updated: March 2016

References

The following references have been used to develop the country profile. It is important to note that contributions are from local, regional and international agencies. The profile is reviewed by the national focal point for accuracy. We encourage you to contact the country contacts (focal points) if any documents cannot be accessed through the links.

- Australian Bureau of Meteorology and CSIRO (2014). Climate Variability, Extremes and Change in the Western Tropical Pacific: New Science and Updated Country Reports. Pacific-Australia Climate Change Science and Adaptation Planning Program Technical Report, Australian Bureau of Meteorology and Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, Melbourne, Australia

- Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific, United Nations, July 2007.

- Pacific Disaster Net

- Forum Secretariat website

- Marshall Islands INDC

- Office of Environmental Planning and Policy Coordination (OEPPC)

- Marshall Islands Climate Change website

- Marshall Islands Meteorological Office

Date updated: March 2016